Autores: Manuel João Ramos

Ano: 2018

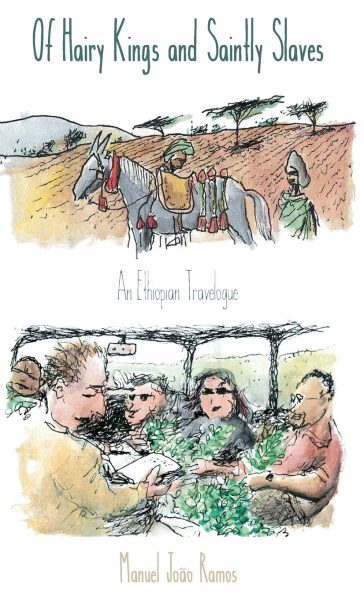

Editora: Sean Kingston Publishing

A lost sketch book on a Portuguese castle rampart left Manuel João Ramos bereft, and the impulse to draw deserted him – but his first trip to Ethiopia reawakened this pleasure, so long denied. Drawing obsessively and free from care, his rapidly caught impressions convey the rough edges of the intensely lived experiences that are fundamental to the desire to travel. For the travel sketch is more than a record or register of attendance (‘been there, seen that’): it holds invisibly within itself the remnant of a look, the hint of a memory and a trace of an osmosis of feelings between the sketcher and the person or objects sketched. Less intrusive than using a camera, Ramos argues drawing comprises a less imperialist, more benign way of researching: his sketchbook becomes a means of communication between himself and the world in which he travels, rendering him more human to those around him.

As he journeys through the Ethiopian Central Highlands, collecting historical legends of the power struggles surrounding the arrival of the first Europeans in the mid-sixteenth century, he is drawn to the Portuguese legacy of castles, palaces and churches, near ruins now, though echoes of their lost splendour are retained in oral accounts. Excerpts from his diary, as well as journalistic pieces, share the conviviality of his encounters with the priests, elders and historians who act as custodians of the Amhara oral tradition. Their tales are interwoven with improvised, yet assured, drawings, and this informality of structure successfully retains the immediacy and pleasure of his discovery of Ethiopia. It also suggests the potential for drawing to play a more active part in anthropological production, as a means of creating new narratives and expositional forms in ethnography, bringing it closer to travel writing or the graphic novel.

Editorial Review:

What do anthropologists do? They sketch! This, at least, is what Manuel João Ramos does in this captivating collection of travellers’ tales and indigenous legends, drawn from his excursions in Ethiopia. Sketchbook in hand, he draws as much as writes, not representing the people and the things he meets, but bringing them irresistibly to life. They explode like crackers from the pages of this book, erupting in a shower of evanescent memories. Why, Ramos asks us, has an anthropology obsessed with visual images forgotten how to draw? And how can drawing and writing be brought together again?

Tim Ingold, Professor of Social Anthropology, University of Aberdeen